Contributions by Asian Americans Through History – Not Widely Known or Published

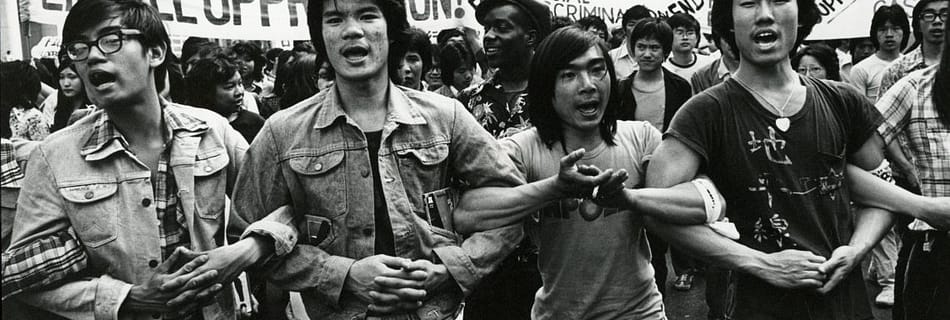

May is Asian American Pacific Islanders Heritage Month Contributions from Asian Americans throughout history are not widely known or published or made to our textbooks. We want to take time to honor these unsung heroes who made such remarkable contributions to our lives. This is a reprinted article from the History website. Originally published on March 31, 2021 by Elizabeth Yuko. We have many resources on our site. Please check out our Asian American Connections or the AAC Journal. If you are local in Rhode Island, we are having a month-long celebration at the Washington Park Library’s patio (outdoor) in Providence on May 6th, May 13, and May 20, 2023 at 1316 Broad Street, Providence, RI. Please register to enjoy this celebration with us. FREE admission, FREE food and FREE educational entertainment! Reprinted article by Elizabeth Yuko from the History Website 8 Groundbreaking Contributions by Asian Americans Through History Though the Gold Rush triggered the first major wave of Asian immigrants to the United States in the 1840s, their presence in America predates the country itself. For example, in 1763, facing a life of forced labor and imprisonment during the Spanish galleon trade, a group of Filipinos jumped ship near New Orleans and established the settlement of Saint Malo, forming one of the first documented Asian American communities in North America. While Americans with ancestral ties to Asia have made countless significant contributions throughout the country’s history, most have never made it into textbooks. From atomic science, to labor rights, to YouTube, here are a few examples of some of the major advancements made by Asian Americans. Atomic Science PROFESSOR CHIEN-SHIUNG WU (LEFT), PICTURED WITH DR. Y.K. LEE AND L. W. MO, HER ASSOCIATES, CONDUCTING EXPERIMENTS, MARCH 21, 1963. In the 1940s and 1950s, Chinese-born physicist Chien-Shiung Wu, Ph.D., was instrumental in the developing field of atomic science. This included the Manhattan Project: the code name for research into atomic weapons during World War II. Specifically, she improved existing technology for the detection of radiation and the enrichment of uranium in large quantities. Following the war, Wu’s research focused on beta decay, which occurs when the nucleus of one element changes into another element. In 1956, theoretical physicists Tsung Dao Lee, Ph.D. and Chen Ning Yang, Ph.D. asked Wu to devise an experiment that would prove their theory on beta decay. Wu did exactly that, but did not receive the 1957 Nobel Prize along with Lee and Yang—one of many examples of her work being overlooked. An early advocate for women in STEM, Wu spoke at a symposium at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964, famously telling the audience, “I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.” Farm Workers’ Rights JULIO HERNANDEZ, UFW OFFICER (LEFT) AND LARRY ITLIONG, UFW DIRECTOR (CENTER) PICTURED WITH CESAR CHAVEZ (RIGHT) AT HIS HUELGA DAY MARCH IN SAN FRANCISCO, 1966. Born in the Philippines, Larry Itliong immigrated to the United States in 1929 at the age of 15 and immediately began working as a laborer, up and down America’s West Coast, as well as in Alaska. By 1930, he joined striking lettuce pickers in Washington, and spent the next several decades working as a labor organizer and eventually, a union leader—including forming the Filipino Farm Labor Union in 1956. In 1965, Itliong and some of his union colleagues organized the Delano Grape Strike: a walkout of 1,500 Filipino grape-pickers demanding higher wages and improved working conditions. As the movement gained momentum, Delores Huerta and Cesar Chavez from National Farm Workers Association joined Itliong and the Filipino Farm Labor Union. Eventually, the two groups combined to form the United Farm Workers, and the strike ended in 1970—but not before making major strides for agricultural workers, regardless of ethnicity. “We got wage increases, a medical plan for farm workers, we set up five clinics, a day care center and a school,” Huerta said in an interview. Civil Rights Though her activism was influenced by the two years she spent in internment camps during World War II, Japanese American Yuri Kochiyama’s civil rights work extended to the causes impacting Black, Latinx, and Indigenous Peoples, as well as Asian American communities. After World War II, Kochiyama and her husband—whom she had met at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas—moved to New York City, where they hosted weekly open houses for civil rights activists in their apartment. “Our house felt like it was the movement 24/7,” her eldest daughter, Audee Kochiyama-Holman told NPR in a 2014 interview. Kochiyama befriended and collaborated with Malcolm X in the 1960s, and continued to work with Black civil rights activists following his death. Then in the 1980s, she, along with her husband, campaigned for reparations and a formal government apology for Japanese American interned during World War II. Their work became a reality in 1988, when President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act into law. “She was not your typical Japanese-American person, especially a nisei [second-generation Japanese-American],” Tim Toyama, Kochiyama’s second cousin, told NPR. “She was definitely ahead of her time, and we caught up with her.” “She was not your typical Japanese-American person, especially a nisei [second-generation Japanese-American],” Tim Toyama, Kochiyama’s second cousin, told NPR. “She was definitely ahead of her time, and we caught up Ethnic Minority Psychology Two Chinese American brothers originally from Portland, Oregon, Derald W. Sue and Stanley Sue, were influential figures in ethnic minority psychology. “Ethnic minority psychology is a subfield of psychology concerned with the science and practice of psychology with racial and ethnic minority individuals and groups,” says Sumie Okazaki, Ph.D., professor of applied psychology at New York University, and author of the book Korean American Families in Immigrant America: How Teens and Parents Navigate Race. In 1972, the Sue brothers founded the Asian American Psychological Association—one year after writing a seminal paper on Chinese American personality. “Derald W. Sue is best known for his work on multicultural counseling and racial microaggression, and Stanley Sue is best known for his work on cultural competence in psychotherapy with Asian Americans and ethnic minorities,” Okazaki explains. The USB INTEL CHIEF I/O ARCHITECT AJAY BHATT, CO-INVENTOR OF USB AND PCI EXPRESS, …

Read more “Contributions by Asian Americans Through History – Not Widely Known or Published”