You can find the original publication of this article at Atelier FU’UNA.

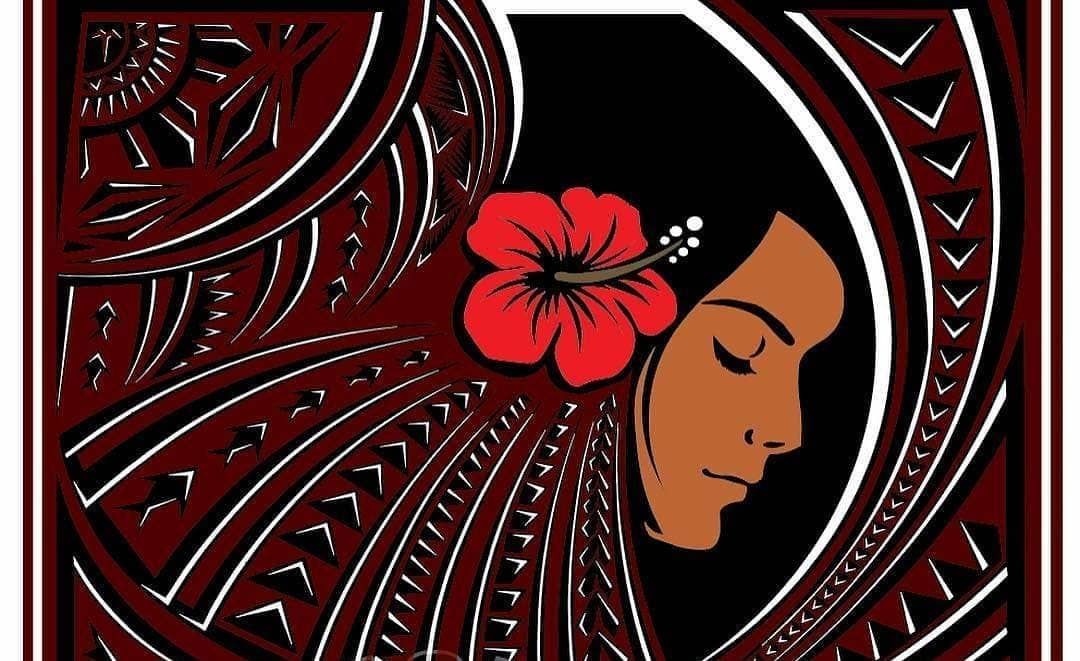

This project is a small, slow effort that is driven by a desire to see more Pacific Islander representation in the visual arts.

Since the age of 16, I’ve taken figure drawing and figure painting courses at Academy of Art College San Francisco (now Academy of Art University), Cornish College of the Arts, Rhode Island College, and AS220. It’s safe to say that I’ve attended well over 100 figure drawing sessions, and every single model I’ve been provided through those institutions was white.

As an undergraduate student, I butted heads with my advisor about being required to take multiple courses that focused solely on European art. I had to create my own independent study so I could research the work of contemporary indigenous artists. Nearly a decade later and Rhode Island College has added one course featuring non-Western arts— that’s eight courses explicitly centered on European visual arts, and one single course to capture all of African, Asian, Native American, Pacific, and of course, European art history.

This Euro-centric focus in art curricula directly mirrors what can be found in museums and galleries. According to a 2019 study, 85% of artists in major US museums are white, and 87% of them are men. It’s no surprise, then, that US museums feature so many portraits of white subjects and nearly no portraits of subjects of color. This especially makes sense in America where fine art and wealth are inextricably linked, and where systems of wealth were designed from the start to extract from rather than build up communities of color. When people of color visit museums, on the rare occasions that we see ourselves represented, they are usually depictions made by white artists and often uphold or in some cases create harmful stereotypes. We’ve been depicted as “savages,” as servants, as objects of fetishization, and in poverty porn. It’s no wonder visitors of color are so rare in most museums. When we do show up, we are often treated like we don’t belong.

The tilted representation in education and in museums upholds whiteness as analogous to wealth, purity, and authority. This visual culture manifests most disappointingly when young artists of color regularly use white women as their default subject of choice.

As someone who has spent over a decade studying, practicing, and working in the visual arts, I’ve dedicated my professional career to building access and representation in the arts for people of color. As an illustrator and portrait artist, humans have always been subject matter that I’ve worked with, but I’ve always wrestled with who to draw and why; as a person who’s experienced mis- and under-representation, I’m especially sensitive to the weight of how and by whom people are represented.

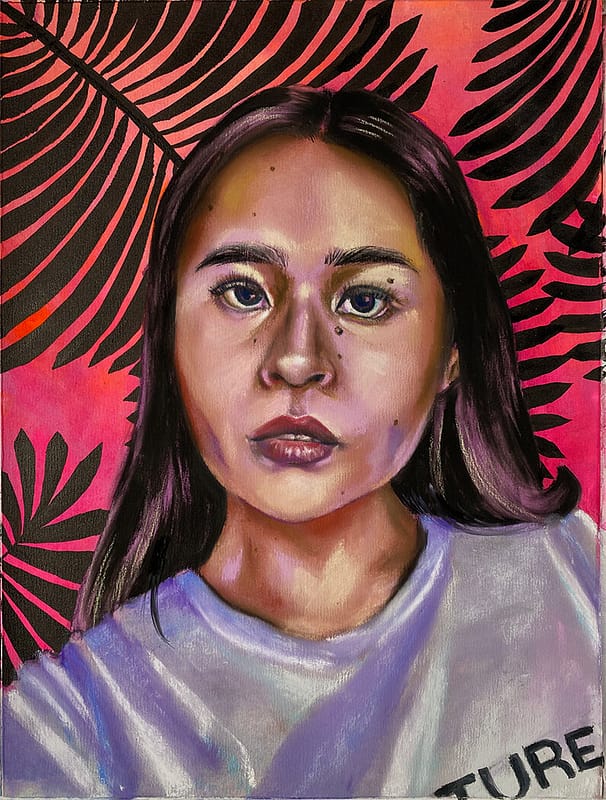

Rather than allow the culture of white supremacy to push me out of the arts, I am emboldened to hold my space. As a Chamoru/i taotao tåno living stateside, I decided to do a portrait series of people of the Pacific diaspora. Through Instagram I finally am connected with others in the diaspora in a way that I’ve never been before, so I used the platform to recruit models. The resulting body of work to date includes seven 9”x12” soft pastel portraits of young men and women from the diaspora, living both on-island and stateside. The simplicity of the compositions is what makes this series radical — no one is hyper-sexualized, no one is performing exoticism. Models were involved in selecting the reference image and were invited to add their voice to the project by providing their own introduction and caption. Each drawing is a love letter to those of us who have been left out of the narratives of art history. We deserve visibility, and to be upheld with care and dignity.

Why Pacific Islanders need visibility now

I began this project in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic when Pacific Islander communities across the country have experienced rates of infection and death disproportionate to our share of the population. There is no national data available to share, because to date the CDC does not collect data on Pacific Islanders; states are not even on the same page about whether to lump us into Asian, or into “Other,” or whether to collect any racial demographics at all. Only 16 states collect demographic data for us, and eleven out of those 16 states demonstrate that when counted separately from Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders are dying at “the highest rates of any racial or ethnic group”. In LA County alone, “Pacific Islanders suffer the highest infection rate of any racial or ethnic group (…) six times higher than for white people, five times higher than for Black people and three times higher than for Latinos(…).” In Arkansas, Marshall Islanders make up only 1.5% of the population and yet as of June of 2020, they made up 38% of the state’s reported COVID deaths.

For Pacific Islanders to be counted as Asians, to be a minority within a minority, is to have our unique experiences effectively erased. Because of this invisibility, our communities suffer real losses. I imagine the term Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) was invented to bring some visibility to us, but it’s become a throwaway term that is responsible for tons of articles, lists, and events with the “PI” notably absent. It also disregards the very real, targeted hate crimes that the Asian American community is experiencing, that Islanders are not. Combining us in a way that’s meaningless does nothing to help any of us.

Race is a construct that was invented and propagated as a tool of white supremacy. It doesn’t take into account the cultural and genetic blending that happens at borders and as a result of human migration. It ignores all methods of self-identification; its intent is to create division and hierarchy. Micronesian, Melanesian, Polynesian, Filipino, Asian and even Chamorro are all terms bestowed upon us by white colonizers. And yet, how we experience life in America or in the territories is completely dependent upon how we are perceived by others. This is why it’s so critical that our narratives are in our own hands.

How you can help

Seven small portraits won’t shake the world, and neither will a post on an artist’s blog. But here are small anti-racist things readers can commit to that can help build visibility for Pacific Islanders as well as Asian Americans:

First and foremost, if you collect demographic data in your work, collect it by ethnicity rather than or in addition to race, and do your best to honor how people identify rather than how they have been described by the United States government.

Be specific when talking about ethnic and cultural groups. Do you really mean Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders? Do you mean people with roots in continental Asia? Do you mean Islanders? Do you mean Vietnamese? Do you mean Carolinians? Do you mean residents of Guåhan? Be as specific as possible.

If you call something “Asian American and Pacific Islander”, make sure you’re actually including Pacific Islanders.

Save acronyms for use in hashtags, not in conversation. Whether it’s ALAANA, BIPOC, NHPI, or AAPI, acronyms quickly become meaningless. Sometimes they can be confusing or unintentionally exclusionary. NHPI for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, for example, is oddly redundant and divisive. So if you want someone to feel seen, name them.

Support movements that reinstate self-identifications. You might not have the chance to vote on something, but you can change how you refer to a place or a people in writing and in conversation.

Follow thought leaders and cultural groups from those communities and listen to the dialogues. No single voice can speak for us all.

As always, support Asian and Islander owned businesses— that includes artists!

Meggai ma’åse to all of the models who took a chance by allowing me to draw their beautiful faces. If you are interested in having your portrait done, check out my “Small Scale” page for more information.

Stevie Merino (Chamoru) “FAMILIAN MESA, DODO CLAN

I am CHamoru. Not half, not a percentage, we don’t do blood quantum here—just CHamoru.

You may see different variations of the spelling Chamorro, Chamoru, but please do NOT say Guamanian—this term was created after WWII to separate between the islands & essentially was used to attempt to erase/whitewash indigenous identity & evolved to be a term that some use to include anyone who lives on Guam including non indigenous folks. I will say I do know a lot of CHamoru elders in the states who use this term still—but this is usually because of their own experiences during that time & as a kid this is what I was taught to use.

Growing up I would tell people I was Guamanian & everyone would say oh Guatemala!?—like [are] you literally correcting my pronunciation & word to something you know instead?!

I taotao tåno (the people of the land), CHamoru are the indigenous people of (Guam) Guåhan. We are part of the Pacific Islander umbrella under Micronesian one of three island categories (Micronesian, Polynesian, Melanesians). Micronesians: the many small islands, there are thousands of small islands in this region. Unfortunately because of our regions small size (amongst other things) we are often missing from many Pacific Islander events/representation/dialogues/and demands.

I feel like my size represents this perfectly in this moment—our island region may be small in size but we are large in spirit & heart (& fight!)

FA’NU’I I DINADDAO-MU — Show your fierceness”

By: Kameko Branchaud

About the Author: Kameko Branchaud, also known as the artist Fu’una, is a descendant of an indigenous village displaced by colonial powers. She is an embodiment of globalization and her illustrative works attempt to process the inter-related influences of history, power, and heritage on the environment and the psyche. The artist earned her MA in Art + Design Education from RISD in 2014 and her BS in Art Education from Rhode Island College in 2013. She has a lengthy history of developing community-based arts programming and a demonstrable commitment to advancing racial equity in the arts. This article is a reprint from its original source website with the author’s permission.