A Brief History of Filipino Americans

By Maia Mongado

On October 18, 1587, men from Manila set foot on what is now known as Morro Bay, California. They were crewmen on a ship that was a part of the Manila Galleon trade, a route between the two Spanish colonies of Mexico and the Philippines. This journey officially made them the first Asians known to ever step foot on what is now American soil.

Filipinos have been present in this land even before modern day America has existed, but the circumstances of this presence has evolved over the centuries. The Philippines’ long history as a Spanish colony ensured that Filipinos would always be present, albeit in small numbers, as crew men for Spanish ships on the outskirts of American trade posts. At some point, some of these Filipino sailors even deserted to create their own small community, Saint Malo, in the Louisiana bayou. Here, experienced with tropical storms and harsh coastal conditions, Filipino sailors (called Manilamen by the surrounding peoples) found a new freedom away from Spanish officials in a quiet fishing village that existed from the early 1800s until 1915, when its last remnants were destroyed by a hurricane.

The bulk of Filipino American history, however, occurred after 1902. Spain and America had just finished fighting their own war; Spain, exhausted an already ongoing revolutionary effort by Filipinos, ceded their territory to America. After a period of brutal fighting between Filipinos and Americans, it ended with a decisive Filipino defeat in 1902. With that, the Philippines America’s largest colony.

From then on, the role of Filipinos in the U.S. would constantly be in flux, governed by the ever-changing identity politics of early 20th century America. As colonial subjects, they were technically American nationals who were unrestricted from migrating to America like many other Asians; many Filipinos received lessons from American schoolteachers, and still today Filipinos have an unusually high fluency of English as a remnant of this colonial past. However, this did not preclude them from experiencing racism, both systemic and personal, from local American populations.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Filipino populations in America rose from a few hundred to 45,000. Almost all men, they immigrated in order to fill demand for cheap farm labor in California or Hawaii during the Great Depression. Americans were not quite sure how to parse their identities; were they Latino, as a former long-time Spanish colony? Were they “Malays” or “Orientals”, racial categories that at the time referred to the general areas of Indonesia and

China? How did anti-miscegenation laws, which forbade intermarriage between races, apply to them? Having been educated as American nationals, Filipino men saw themselves as having the same rights as any other American, wearing flashy, fashionable clothes and dancing with white women in local dance halls. This drew the ire of white men, who decried what they saw as the theft of their women and their jobs by arrogant immigrants. Mounting tensions led to the 1930 Watsonville Riots, in which white men wandered in mobs, attacked and beat Filipino men for these perceived slights.

Such tensions led the American government to speed up the independence process for the Philippines and restrict Filipino immigration to the United States. In 1946, the Philippines was officially no longer an American colony; however, this did not stop many Filipino veterans from successfully applying for American citizenship and settling in the U.S. with Filipina brides. Filipino women and children encouraged the creation of local clubs, associations, and

neighborhoods. The family structure, always the lifeblood of community in the Philippines, was now present in America. Filipino communities took on a new vibrancy and unification, and many Filipino American districts blossomed throughout the U.S., concentrated on the west coast. After the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act ended all national quotas, the number of Filipinos in the U.S. skyrocketed to the now 4.2 million living here today.

Filipino Americans today come from all walks of life and many different origins. Some have had family living here for generations, where others have immigrated themselves in the past few years. Because of American influence on Filipino history which has given Filipinos a unique ability to assimilate, Filipinos are sometimes thought of as a “silent minority”; they have not been as represented in popular American media and culture as much as groups such as Chinese, Japanese or Indian Americans, despite their large numbers.

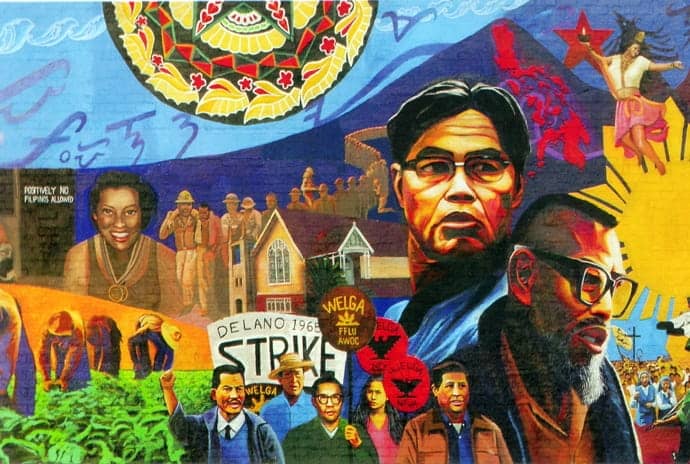

However, this has not stopped Filipinos from forming lively communities and connecting with one another, even oceans away from home. Although Filipino American history has been fraught with racialized violence from the U.S. government and populations, it has also been one of resilience, adaptability, and interconnection. Filipino Americans have always been at the forefront of important movements, such as Larry Itliong, who worked with Cesar Chavez to fight for Filipino and Mexican farm workers’ rights in the 1960s. Or Fe del Mundo, the first woman to be admitted to Harvard Medical School. The history of Filipino Americans also expose how weak the racial divisions we form in the U.S. truly are; they have historically not been able to be categorized and still today exist in a sort of flux between various identities. In a world of globalization, as racial, ethnic, and national identities reach a new point of fluidity, the history of Filipino Americans perhaps has a valuable lesson to teach us all about the importance of human connection above all superficial division.

Sources

July 4, 1946: The Philippines gained independence from the United States: The National WWII

Museum: New Orleans. The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. (n.d.). Retrieved October

22, 2022, from

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/july-4-1946-philippines-independence

Manilamen the Filipino settlement: Lesson Plan curriculum: The Asian American Education

Project. Manilamen The Filipino Settlement | lesson plan curriculum | The Asian American

Education Project. (n.d.). Retrieved October 22, 2022, from

https://asianamericanedu.org/manilamen-first-asian-american-settlement.html

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved October 22, 2022, from

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/war

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, August 15). Watsonville riots. Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22,

2022, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watsonville_riots

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, October 1). Larry Itliong. Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22, 2022,

from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_Itliong

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, October 18). History of Filipino Americans. Wikipedia. Retrieved

October 22, 2022, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Filipino_Americans

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, October 21). Philippine Revolution. Wikipedia. Retrieved October

22, 2022, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippine_Revolution

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, October 8). Filipino Americans. Wikipedia. Retrieved October 22,

2022, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filipino_Americans

About The Author: Maia Mongado is a senior at Brown University majoring in Computer Science. She has also taken coursework in English, French, and Filipino studies. Historically, she has worked as a tutor for refugee children from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and has been involved in the Filipino Alliance of Brown University as a freshman representative. She is passionate about writing about social justice and its connection with global politics and modern technology. In her free time, she loves to cook, read, and go on long walks around the city. She is excited to make a change in the local Rhode Island community with CSEBRI!